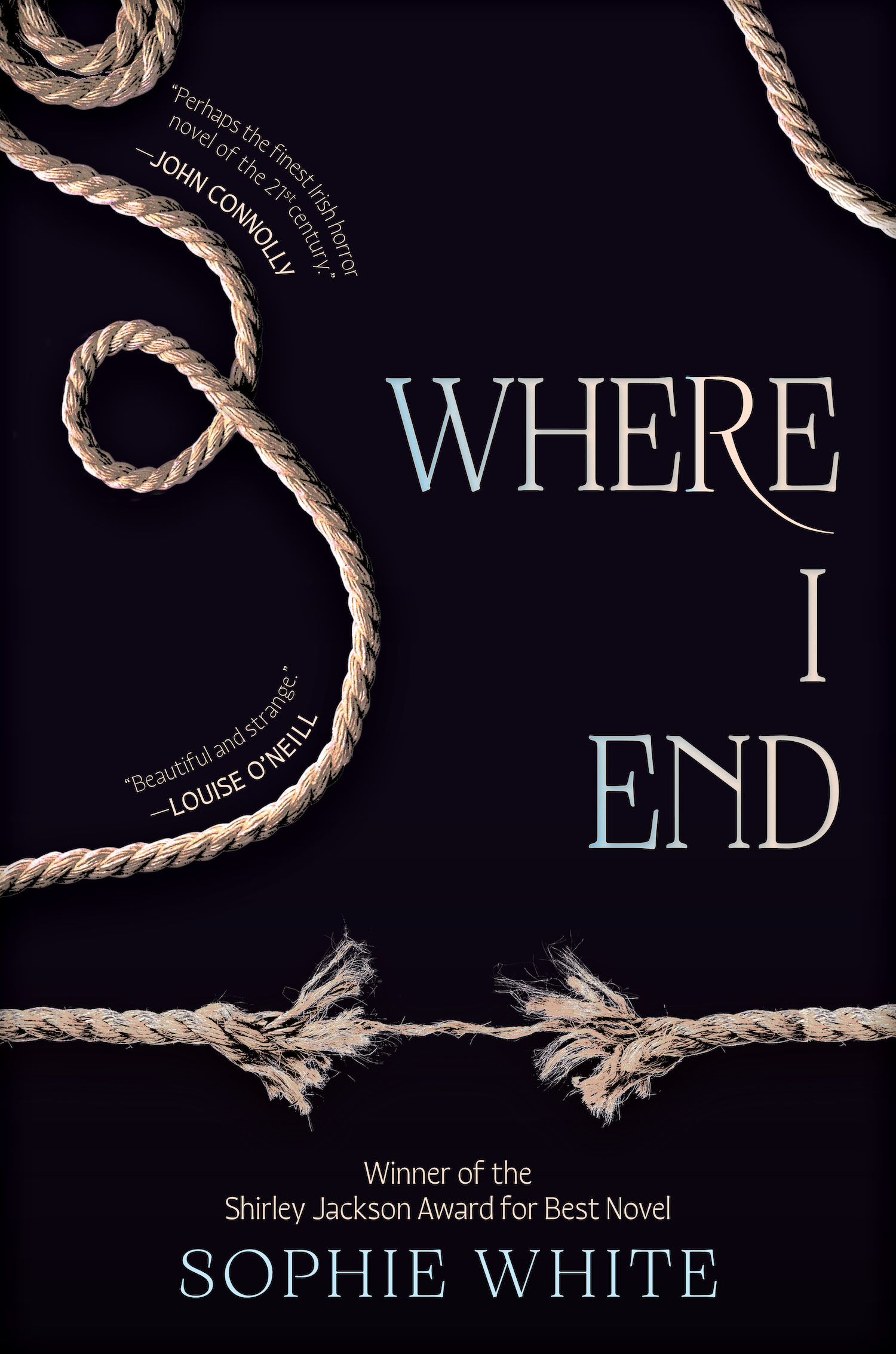

Erewhon Books announces Sophie White’s horror debut Where I End, a modern gothic horror forthcoming in Fall 2024. We’re thrilled to share the cover and an exclusive excerpt below!

At night, my mother creaks. The house creaks along with her. Sometimes in the morning we find her in places. We never see her move. We just come upon her.

Aoileann is cursed. She has no friends, never gone to school. She has never left this windswept craggy isle off the coast of Ireland.

Her mother is cursed: a silent wreck Aoileann calls the “bed-thing.” Alongside her grandmother, Aoileann’s days are an endless monotony of feeding, changing, and caring for the bed-thing.

Their island seems cursed, whispering secrets only Aoileann hears. Then Rachel, a vivacious artist from the mainland, arrives with her colicky newborn. Rachel arouses yearnings Aoileann cannot fully comprehend. Soon, the unfolding of her mother’s secret tragedy and Aoileann’s pursuit of her own dark desires are both destined to unleash a maelstrom upon all three of their lives.

Described by New York Times–bestselling author John Connolly as “perhaps the finest Irish horror novel of the 21st century,” Where I End is a modern Irish gothic that will pull readers into its undertow of family resentments and relentless obsession.

Buy the Book

Where I End

I am so excited to be working with Diana Pho and the whole team at Erewhon who are unleashing my creepy little book on an unsuspecting new audience. I am especially excited that this distinctly Irish novel will be making its way into the hands of readers complete with all the original language and awful traditions (some real and some imagined) unique to my country! Where I End has made an incredible journey across the Atlantic, first it was championed by incomparable horror maven, Ellen Datlow. Then it received the ultimate recognition in winning the Shirley Jackson Award (particularly apt as I am so inspired by Jackson’s work), and then it found its American home at Erewhon. I hope new readers will enjoy being transported to the wild and dreadful island of my dreams and discovering the horrors that dwell there alongside the terrible beauty.

—Sophie White, author of Where I End

After winning the Shirley Jackson Award, one of my Erewhon colleagues reached out to me and said, ‘This is a perfect horror gem–we must get this!’ And indeed, WHERE I END is a harrowing character study that exposes a raw nerve between mothers and their children, revealing the terror of growing old and being a burden on those who are supposed to love you. The story is a tight, claustrophobic and psychologically-twisted slice into Aoileann’s mind. I ate this up, and hope US readers do too when it hits bookshelves this autumn!

—Diana M. Pho, Executive Editor with Erewhon Books

The island is dark but the sea is dark too, though it is made of something else entirely. It is silky and each undulation and ripple is edged in what little shy lustre can be drawn down from the endless sky-hole above. The sea is dead, gilded with the dead light of dead stars and, because it sways and sings and chants, it feels alive, although it’s not. It is teeming with death and it is very, very beautiful. At the base of the cliffs at the west end, it licks and laps down under the island’s hulk. At the east end, it rolls up onto the beach like a lover ready to be taken.

The sea is death reanimated. Down under the shim- mying surface, the currents conduct the corpses and they sway in a dance, ringed around the island’s underbelly.

On each exhale, the sea draws back and the island-wreck appears to rise and rise. The islanders are doomed passengers, their homes like molluscs clinging to the stone deck. It is all so precarious. One hundred and thirty-four fleshy hearts beat inside fleshy bodies inside toppling stone dwellings, all at the mercy of this dead and angry thing. The smallest heart on the island is the size of a walnut and it belongs to Rachel’s baby. To end its delicate throb, you would need only a pinch of a thumb and fore- finger. A firm press to pop it like a berry. Every scrap of life on this island is fighting hard in its own little struggle.

It seems useless to even try in this hateful place. The thing in the bed may even have the right idea: to succumb, to beg, to be ended. The thing in the bed is maybe privy to some- thing. Or perhaps is just more willing than the others to face what this place is capable of.

The others know but they turn away from this knowledge. Out loud they call them accidents. Out loud they call them bad luck. The island records are untrustworthy things, as the museum curators are learning. All that’s known for absolute certainty is that no census taker came until 1931.

Mainlanders hated the island because, going back generations, stories about it murmured through their families, spreading unease.

‘The Islanders didn’t have eyes,’ said the stories. Instead, they had two watery boreholes that contained nothing. Looking into the eyes of an islander was like looking straight through to the milky sky behind them; the expanse would devour you.

Never look at them when they smile, warned the old people.

The stories lacked detail, though. They were blank things. The horror was in the blankness. The horror was in the gaps.

‘Islanders pulled grateful survivors from the sea,’ the stories said. ‘Saving them from drowning only to deliver them to a worse end.’

Never let them show you their smile.

Never look inside the mouth. Never see inside them. ‘The island makes people do things,’ they said.

With bloodless, spidery hands, Islanders drew the frightened near-drowned from the shore and led them up to the island’s interior.

The island made people do things, said the old people. From there, the islanders would let go of the salvaged person and stand back. They didn’t need to do anything more, but they’d stay to watch.

They roamed close, tracking the unfortunate person as they stumbled on upwards.

The island made people do things, said the old people. The islanders witnessed the island.

* * *

By the time the first census was recorded, the mainlanders had settled on more ho-hum aversion: the islanders were ugly; they were poor; their Irish was incomprehensible. In spring 1931, the island was home to 187 souls. About ten families, all fishing and living a spartan existence.

The following year, when the man from the department returned to check some details, he found the population had dropped abruptly to 166. Twenty-one people unaccounted for. When the islanders were unforthcoming, the census taker took the matter to mainland authorities.

They made the trip to investigate. The note-taker recorded a little of what went on during the questioning.

The island seems to be some kind of breacghaeltacht, but what’s spoken there is a dialect barely related to Irish.

Those we did understand seemed unperturbed by what appears to have been a mass death of 21 people since March of ’31.

We were brought to the island’s rudimentary ‘cemetery’ (located on the island’s high exposed north- east side, see marked map on file). The practices around burial are unusual. We are told by Rionach (girl, about 17) that they cannot dig the island – at its deepest the soil layer is barely a forearm’s length – hence their ‘solution’. Island children play in the area and appear unfazed by the macabre spectacle to be found there.

Rionach intimates that the island suffers losses of this scale frequently due to the dangerous nature of fishing the surrounding waters.

When it was pointed out that if this were the case, then the island’s population would have died out long ago, the girl ceased to cooperate.

Some of the missing appear to correspond to ‘graves’ and testimony from islanders claiming to be surviving family, would it seem, corroborate this. However, there are at least seven others entirely unaccounted for.

Inconsistencies in the record may be at fault. But even with some error or doubling up, we are still looking for the bodies of at least five people, some of whom appear to be members of the same family. When this is put to the group we assembled outside the island’s shop, one elderly man (60s–70s approx.) answered:

‘If a man goes and chooses to take his clan with him, what do we do?’

So it would appear that some migration takes place in the community.

The island made people do things, said the old people.

And maybe, yes, for the island to remain so cold to what it has witnessed, it must have some hand in it.

Excerpted from Where I End, copyright © 2024 by Sophie White.